Kessels, a renowned Dutch company with its origins dating back to the late 19th century, is a remarkable name in the world of musical instruments and music publishing. Founded by Mathijs (Mathieu) Kessels, the company’s journey was marked by innovation in wind instruments, expansion into the broader music industry, and numerous challenges, including financial setbacks and changes in leadership. Throughout its history, Kessels played a crucial role in shaping the evolution of musical instruments in the Netherlands and left a lasting impact on the musical landscape.

A Dutch musical instrument factory

Mathijs (Mathieu) Kessels, born in 1858, embarked on his entrepreneurial journey in 1880 when he established a music publishing business in his hometown of Heerlen. However, the lure of expanding opportunities in the city of Tilburg, coupled with his brother Joseph’s appointment as director of the wind orchestra “Nieuwe Koninklijke Harmonie” in Tilburg in 1884, prompted Mathijs Kessels to relocate his business to Tilburg in 1886.

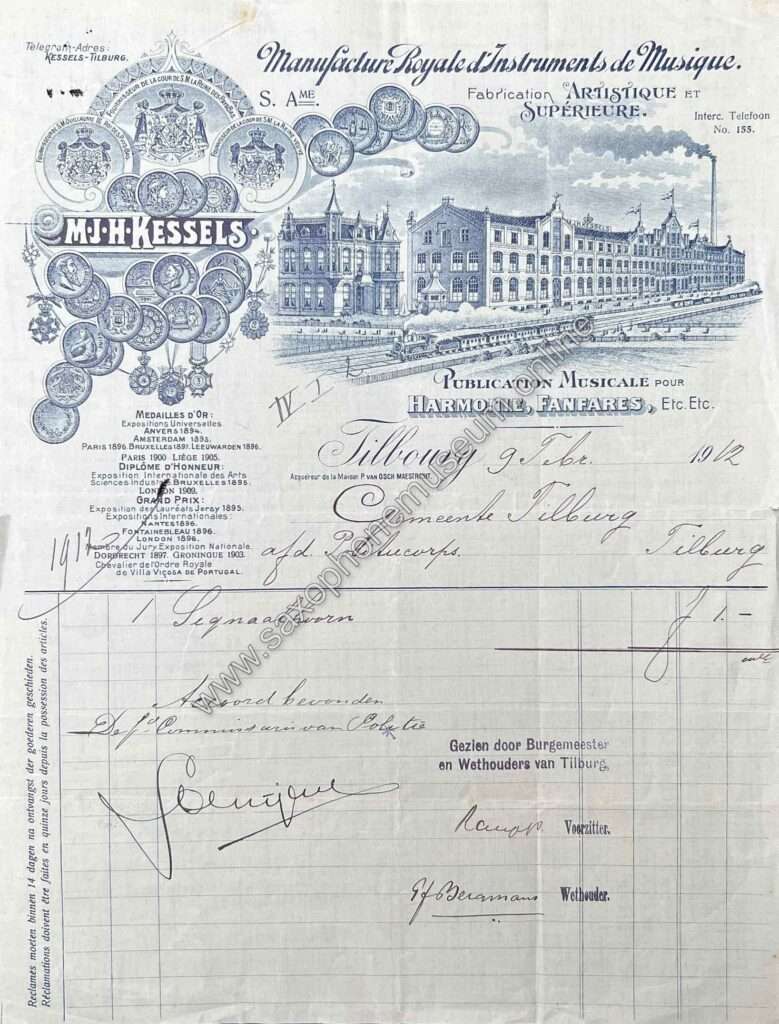

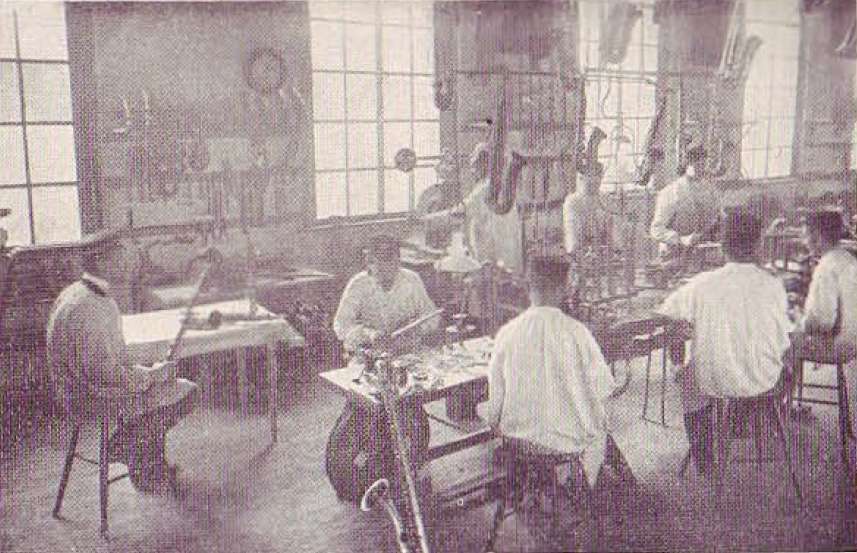

By 1887, Kessels had enlisted the assistance of two German craftsmen who specialized in instrument repairs. In May 1889, an advertisement in his music magazine, the ‘Muziekbode,’ introduced the “Nederlandsche Fabriek van Muziekinstrumenten,” initially focusing on brass instruments before expanding to include saxophones and other wind instruments. The Tilburg Chamber of Commerce reported the company’s success by 1891, with a growing workforce and orders pouring in from both domestic and international markets.

Facing space constraints, Kessels built a new factory in 1897, adjacent to the railway to Turnhout, Belgium, and established an in-house printing house for his publishing business.

Models and innovation

In 1894, Kessels introduced significant improvements to their wind instruments, which they branded as “Perfectionné.” The following year, a new and enhanced model designed as a “solo instrument” was released under the name “Prototype.” These instruments garnered great success when showcased at the 1896 World’s Fair in Brussels. However, the Paris-based company Besson raised objections regarding the use of the name “Prototype,” as they also had instruments with the same name in their portfolio, leading to a legal dispute with Kessels. While Kessels was vindicated twice in court battles, after the final trial, they decided to discontinue the “Prototype” name. Subsequently, Kessels rebranded their wind instruments as “Célesta” and “Sirena.” Continuous research was conducted to enhance the instruments, including adjustments to bore, airway, proportions, and intonation. In 1915, Kessels’ new factory commenced manufacturing instruments named “Eola” and “Corona.” Their product catalog included both standard models and the aforementioned premium options.

The 1899 catalog sheds light on the various tunings available at that time. It mentions the “new / normal” a (“La”) of 870 Hz (435 Hz) and the “old (or English) a of 902 Hz (451 Hz). In addition, 888 Hz (444 Hz), 868 Hz (‘old French La’ (434 Hz)) and 921.7 (‘high La’ (460.85)) were available. All these different tunings certainly cause quite a bit of confusion today when playing old instruments.

Financial struggles

In the early 1900s, expanded its manufacturing repertoire beyond wind instruments, venturing into the production of pianos, harmonicas, and string instruments. In 1902, Kessels sought to grow but faced a setback when the Tilburg bank, a long-time partner, went bankrupt, prompting the establishment of a partnership, later known as ‘M.J.H. Kessels,’ in May 1903 with wool merchant Ferdinand Hoosemans. An “unfortunate decision” according to Kessels himself. This partnership involved ambitious plans to export pianos to England, which ultimately proved to be a costly misstep, leading to liquidity issues in 1907. Advertisements touting bargain pianos appeared in various magazines and newspapers of the time. To address financial woes, Kessels was forced to transform his business into a stock company in 1908, with backing from the Rotterdam-based bank Marx & Co.

Unfortunately, these financial efforts did not improve the company’s situation. The new London branch’s struggles further deepened Kessels’ reliance on the bank, particularly under the increasing influence of director van Ommeren, who ascended to the position of the president of Kessels’ supervisory board.

In 1913, ‘M.J.H. Kessels’ received the distinguished designation “Royal,” and in 1914, it rebranded as ‘N.V. Koninklijke Nederlandsche Fabriek van Muziekinstrumenten, voorheen M.J.H. Kessels.’

Leadership changes

Nonetheless, in the same year, Mathieu Kessels faced expulsion from his own company after a power struggle orchestrated by Van Ommeren. The immediate cause is the mobilization of 1914, which diminished the demand for musical instruments. Despite Kessels’ valiant efforts to rescue his business, the situation soured when Van Ommeren attempted to appoint a second director, Willem König, leading to Kessels’ dismissal.

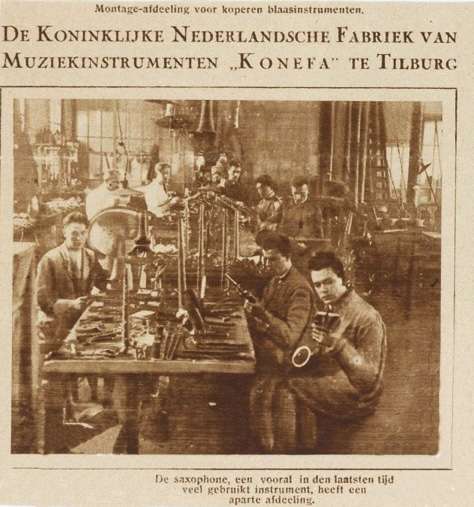

Willem König became the managing director, overseeing a period of poor results and strained internal relations. In 1924, the company dissolved, and on the same day, former employees established N.V. Nederlandsche Fabriek van Muziekinstrumenten KONEFA (N.V. KONEFA). In 1930, König relocated the music publishing business to The Hague, followed by branches in Rotterdam and Waddinxveen. Four employees continued the musical instrument factory,

In 1934, there are still 12 employees, who actually work as on-call workers. On December 1, 1939 bankruptcy is declared.

A new beginning

Mathieu Kessels did not give up after being expelled from his company in 1914. Rather, he swiftly established a new factory. On September 19, 1915, this new facility, named “Nederlandsche Fabriek van Muziekinstrumenten,” opened its doors, located opposite the 1898 factory. In the same year, he also initiated a new magazine, “De nieuwe muziekbode.”

In 1931, due to legal circumstances, Kessels was compelled to change the factory’s name to “Nationale Fabriek van Muziekinstrumenten.” Following this adjustment, Kessels displayed a sign with the updated name: “Nationale Fabriek van Muziekinstrumenten, sole proprietor M.J.H. Kessels.”

The Kessels family

In 1932, Mathieu Kessels passed away, and the estate was divided in 1933. Mathieu Kessels Jr., born in 1896, the eldest of Kessels Sr.’s three sons, assumed control of the musical instrument business. He continued to manage the business for a period in Grathem, Limburg, although subsequent details about its history remain limited. Paul Kessels, the second son (born in 1901), took over his late father’s music publishing business in 1933 and, on July 12 of that year, founded “De Muziekuitgaaf (der Nationale Fabriek van Muziekinstrumenten).” During World War II, with the establishment of the ‘Kulturkammer,’ he discontinued the publishing business, which eventually closed in 1958.

Hendrik Kessels, the third son (born in 1903), initiated the Kessels musical instrument factory at Waldorpstraat 68 in The Hague in 1931. In 1934, this factory was relocated to Maastricht. Despite his reputed craftsmanship, Hendrik faced business challenges due to his limited understanding of business and poor handling of money. In 1939, he returned to Tilburg with his family. On January 2, 1940, he took ownership of “Kessels Vereenigde Muziekinstrumentenfabriek,” situated in his father’s former factory at Industriestraat 46. This company was dissolved in December 1954.

The murder of Marietje Kessels

Notably, among the six sisters of the Kessels family, the one who stands out in the memory of Tilburg is Maria Catharina Wilhelmina “Marietje” Kessels, born in 1889. Tragically, Marietje’s life was cut short when she was murdered in the Noordhoek church in Tilburg on August 22, 1900, at the tender age of 11. The lingering uncertainties surrounding the circumstances of her murder continue to resonate within the Tilburg community. In 1988, Tilburg author Ed Schilders authored the book “Moordhoek,” delving into the events of Marietje’s murder. In 2011, “The Murder of Marietje Kessels” was published by Godelieve Kessels, the daughter of Mathieu Kessels Jr., in which she alleges the involvement of the pastor of the Noordhoek church as the culprit.

Learn more

Kessels Museum Tilburg | The history of the Classical Saxophone in the Netherlands (book)

References

de Brouwer, L.F.P.M. (1993). Inventarissen van de Archieven van de Muziekinstrumentenfabrieken en Muziekuitgeverijen van M.J.H. Kessels en hun Opvolgers (1871) 1881-1957 (1068), Gemeentearchief Tilburg.

Passier, E. (2013). De opmars van de muziekindustrie: Kessels en Passier, ondernemers met passie voor muziek, Stichting Wie Wat Bewaart Heeft Wat.

De Nieuwe Muziekbode (no. 3, 1931). Het Ontstaan der EOLA en CORONA instrumenten.

M.J.H. Kessels, Catalogue (1915).

M.J.H. Kessels, Catalogue (1899).